Wednesday, July 29, 2015

Past Haunts

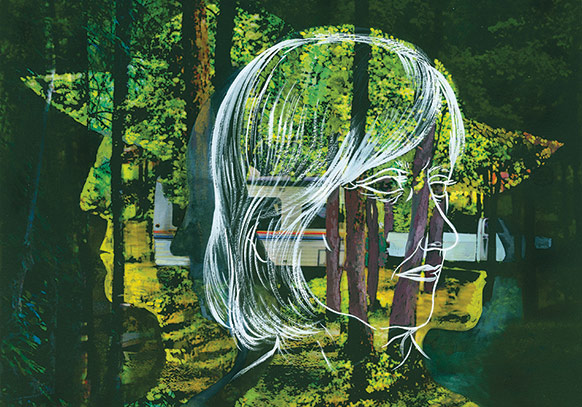

I left Indiana and Purdue University in 2008, once I finished my PhD. I was 30 years old, and I was so happy to be going home to California after five years in the shadow of cornfields, tornadoes, and loves lost, begun, and discarded. Earlier this week, after seven years, I returned to Indiana for the first time for a conference on the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas--an annual conference that my friends and I began here at Purdue ten years ago, and which has flourished ever since. We came home for our tenth anniversary.

Nostalgia always brings us home.

Coming "home" is such a complex thing. We come happily, expectant, but we also cannot help but remember the conflicts and violences that spattered themselves across our lives. This afternoon I attended a talk by a friend and colleague who referenced the work of Edward Casey--particularly his work that deals with memory and its connection to place. I couldn't help but think of this place, where I sit now. I was 26 when I first left California to start graduate school--young, unaware, mistakenly married. There were others like me--those who had married young, before we had become who we were meant to be. The rate at which we--poets, writers, thinkers, teachers--all transformed into our selves was staggering. Many of us left someone behind in that transformation. The ones left behind lost their place in our new world. It was liberating, yes, but it was also not without the infinite sadness that always accompanies such a moving on, such a splintering. I'm so sorry. Splitting at the root aches indefinitely, even when it is necessary in order for growth to begin.

I left and found love in this place. Here, I discovered that some love is little more than obsession--intoxicating, often, but toxic always. In this place, I learned that you can love and hate someone simultaneously. Then I found love again while anchored to this place, only to uncover duplicity and betrayal.

Of course I've never forgotten any of this. It's not as if I'm remembering it for the first time, now that I'm back here briefly. But there's something about place, and how it affects the way memory materializes, the way it touches us. We leave a place, and put down roots elsewhere--we become skinned of memory. And then if we are wise or foolish enough to return to that place, to the site of trauma, it burns as the memories materialize.

But I've never minded the fire. The loves found and lost while I was here were all part of being in transit. Looking back on those years from this point in time, from a position of authentic love and happiness, is uncanny, though. It's hard to reconcile my many lives, the many drafts of myself. My impulse is to find meaning in the current shape of my memories, but it always drowns in meaningless and transgressive cliche: it all happened for a reason, it made me who I am, I am full of regret, I have no regrets, it allowed me to appreciate who I am and what I have now.

There is no meaning in these memories; I simply bear witness to them.

Tuesday, April 07, 2015

My Grandmother

Her body is so slight now at 80 pounds. Bones pushing through paper skin. How is it that her eyes have grown so large while her body and mind devolve? One wonders what she sees with those once beautiful eyes, now void, desperate. Perhaps one prefers not to know. Perhaps I prefer not to know. Does she see us for who we really are? It's in all the best literature: the madwoman who sees everything, and prophesies, foretells our future. And, it's true, I think, as I stare brazenly at my grandmother: her body, memory removed and reconfigured, tells my future. At least that's what I'm afraid of--that I am seeing her the way I will one day be seen. My mother, though--her fear sinks a layer deeper into her than mine does. I see that, even though she doesn't say it.

If my grandmother's the madwoman I've found in so many narratives, I want to know what it is that she knows. Does she know that I told myself I wouldn't go see her again after the last time? Does she know how brilliantly the shame bloomed inside of me when I admitted to myself that I didn't want to go back? That I didn't want her to mistake my hand for a piece of chocolate again? That I didn't want the expression of horror, etched as deep as the bones in my face, to scare her? I remember the days right before she was taken to a home. Do we really dare to call such a place a home? My grandfather, hip shattered, lay in the hospital, and she, his wife, wandered aimlessly around my parents' home.

Daddy? Where did Daddy go?

She kept asking that question, tugging on the sleeves and pant legs of anyone close enough, fiddling anxiously with the buttons on her holiday flannel pajamas. When the wandering became too much for us, we made her sit in a wheelchair. We felt guilty. We made excuses. My brother and I broke into a fit of hysterical laughter after looking for ways to entertain her, and finally settling on a ridiculous impromptu dance routine. Grandma, do you like our dance? Laughter always hides something. Some people, some families, are better at the hiding part than others are. Horror, in this case, is what we hide.

She hasn't known us for some time now. But that night, the night we danced our ridiculous dance for her, she reached for my hand and squeezed it with her little claw-like hands and said, suddenly: don't forget about me, don't forget about me. As if she'd had the briefest moment of clarity, as if she'd caught a glimpse of what was happening. The shame bloomed inside again, because I realized that I want to forget.

He'll be back, we'd say, when she asked for "daddy" hundreds of times, over and over and over and over. Don't worry. The false reassurances we often give young children coming back to haunt us in old age, rounding out our sharp little lives in ways we'd never considered. We would like to protect her--from what we have no idea.

I keep waiting for that call, my grandfather says, a few months later as he recovers from his fall in my parents' home, while my grandmother becomes smaller and smaller in a home that isn't her own. And suddenly I can't decide which breaks my heart into more pieces: my grandmother, with her memories jumbled and fragmented; or my grandfather, severed from the woman with whom he has spent his entire adult life, his memory and mind intact enough to feel pain and fear and guilt and the threat of complete loss.

And I think to myself, I spent a good portion of my life waiting for those calls--expecting them at every turn. My mother? My father? One of my brothers or my sister? What foolishness. How vile the memory of such fears becomes when I see what it means to really wait for that call. When abstract fears become known.

My mother, then. I feel tightness in my chest when I imagine what she is experiencing, as she cares for her elderly father and his very sad heart, and also begins to grieve for a mother who is simultaneously alive and dead. This is what makes dementia and diseases of the mind so horrifying: loved ones are necessarily in a constant state of mourning. We face the loss every day that we stare into blank eyes. It faces us, taunts us. But death is yet to come so we have nothing to bury. We aren't allowed to move on just yet. We simply mourn daily; it becomes our most careful routine. I've been watching my mother mourn for quite some time now--this while she is pulled by other looming losses and struggles having nothing to do with my grandmother. Why must the universe unload on us all at once? There is no divine plan. This is life. This is our life.

I'm thinking of all this, a few days into Passover, and I realize that the sea doesn't always part. We don't always move through the water without drowning. Some of us will make it--we swim hard, or we float miraculously. But others will drown.

If my grandmother's the madwoman I've found in so many narratives, I want to know what it is that she knows. Does she know that I told myself I wouldn't go see her again after the last time? Does she know how brilliantly the shame bloomed inside of me when I admitted to myself that I didn't want to go back? That I didn't want her to mistake my hand for a piece of chocolate again? That I didn't want the expression of horror, etched as deep as the bones in my face, to scare her? I remember the days right before she was taken to a home. Do we really dare to call such a place a home? My grandfather, hip shattered, lay in the hospital, and she, his wife, wandered aimlessly around my parents' home.

Daddy? Where did Daddy go?

She kept asking that question, tugging on the sleeves and pant legs of anyone close enough, fiddling anxiously with the buttons on her holiday flannel pajamas. When the wandering became too much for us, we made her sit in a wheelchair. We felt guilty. We made excuses. My brother and I broke into a fit of hysterical laughter after looking for ways to entertain her, and finally settling on a ridiculous impromptu dance routine. Grandma, do you like our dance? Laughter always hides something. Some people, some families, are better at the hiding part than others are. Horror, in this case, is what we hide.

She hasn't known us for some time now. But that night, the night we danced our ridiculous dance for her, she reached for my hand and squeezed it with her little claw-like hands and said, suddenly: don't forget about me, don't forget about me. As if she'd had the briefest moment of clarity, as if she'd caught a glimpse of what was happening. The shame bloomed inside again, because I realized that I want to forget.

He'll be back, we'd say, when she asked for "daddy" hundreds of times, over and over and over and over. Don't worry. The false reassurances we often give young children coming back to haunt us in old age, rounding out our sharp little lives in ways we'd never considered. We would like to protect her--from what we have no idea.

I keep waiting for that call, my grandfather says, a few months later as he recovers from his fall in my parents' home, while my grandmother becomes smaller and smaller in a home that isn't her own. And suddenly I can't decide which breaks my heart into more pieces: my grandmother, with her memories jumbled and fragmented; or my grandfather, severed from the woman with whom he has spent his entire adult life, his memory and mind intact enough to feel pain and fear and guilt and the threat of complete loss.

And I think to myself, I spent a good portion of my life waiting for those calls--expecting them at every turn. My mother? My father? One of my brothers or my sister? What foolishness. How vile the memory of such fears becomes when I see what it means to really wait for that call. When abstract fears become known.

My mother, then. I feel tightness in my chest when I imagine what she is experiencing, as she cares for her elderly father and his very sad heart, and also begins to grieve for a mother who is simultaneously alive and dead. This is what makes dementia and diseases of the mind so horrifying: loved ones are necessarily in a constant state of mourning. We face the loss every day that we stare into blank eyes. It faces us, taunts us. But death is yet to come so we have nothing to bury. We aren't allowed to move on just yet. We simply mourn daily; it becomes our most careful routine. I've been watching my mother mourn for quite some time now--this while she is pulled by other looming losses and struggles having nothing to do with my grandmother. Why must the universe unload on us all at once? There is no divine plan. This is life. This is our life.

I'm thinking of all this, a few days into Passover, and I realize that the sea doesn't always part. We don't always move through the water without drowning. Some of us will make it--we swim hard, or we float miraculously. But others will drown.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)