I just read a piece called "Nothing is Illuminated" by Hal Niedzviecki, who I have never heard of. It's shockingly insensitive, and downright ignorant on most counts. I posted a response, and have copied it below:

Are you attempting to coin a new term with "Holocaust Style"? If so it feels more than a bit ignorant. For at least the past decade, in the literary world and beyond, what you are referring to has already been labeled and defined as Post-Holocaust Literature. You may consider reading up on the genre as a whole, including the fairly large body of scholarly work that has been done on it. The narratives of Second Generation (children of survivors) writers, like Thane Rosenbaum and David Grossman among others, have also garnered the attention of scholars working in psychoanalytic criticism and trauma theory. Attempting to call it "Holocaust Style" trivializes the content and suggest that there's some sort of mimicry or bizarre obsession involved with the construction of these texts. What your comments seem to ignore is the fact that, like it or not, the Holocaust happened, and it now colors everything we say and do, particularly for those in the Jewish world -- it's a legacy of loss and destruction that we're stuck with, and to suggest that we should cease speaking/writing about it is like a slap in the face to those who died in it, lived through it, or have family members who experienced it. But considering that you are fed up with actual images and stories from the camps, I would think you would be able to appreciate the Post-Holocaust narratives of people like Rosenbaum and others who show us the after-effects of the Holocaust without relying on standard images of corpses and gas chambers.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Fair Warning and Fair Weather

I just flew into LA last night and realized something frightening: I have acclimated to life in the midwest. You know that you are no longer a southern Californian when you are sitting in traffic on the 405 freeway at 8:45pm and you can't figure out what the problem is. I kept asking myself, "What is all this traffic? Is there an accident?" Of course, after an hour or so I remembered that rush hour traffic is pretty much from 3:30-9:00pm in Los Angeles. I also realized that I was no longer a southern California girl as I praised the beautiful, 55 degree night time weather during dinner with my friend, who was shivering uncontrollably because of the "cold."

At any rate, I'll be here for a few weeks, trying to re-acclimate myself to so Cal life. So here's fair warning: don't expect many blog posts for a while!

At any rate, I'll be here for a few weeks, trying to re-acclimate myself to so Cal life. So here's fair warning: don't expect many blog posts for a while!

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Trading Whores for Sorrow

I had a lovely experience over the Thanksgiving holiday: starting and finishing a book that has nothing to do with my dissertation. After reading my friend Casey's review of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Memories of My Melancholy Whores a few months ago, I decided to read it myself. It was strange, and strangely inviting -- often dark, but always in the context of lush, descriptive language. The story of a ninety-year-old man who desires an evening with a young virgin, the novella is very much about the fear of aging and of being old, and the things we consider doing in order to entertain the possibility (or the illusion) of youth even for a moment. But it's also about torment, I think, and about the tendency of some people to entertain, even feed, their own personal torments, their own well-cultivated sorrows. At one point, the old man realizes that he is dying of love for the young virgin, but he also realizes that the contrary is true: that he "would not have traded the delights of my suffering for anything in the world" (84). I think I know people like this -- people who relish and prolong their sorrows more than their joys; perhaps I have caught even myself doing such a thing. But what is rare is to hear someone say, "This, this sorrow, is what I desire, is what keeps me alive, is what becomes my joy."

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Holiday Reading

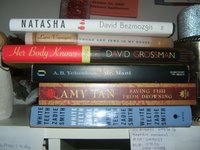

I have an excel spreadsheet with over a hundred books that I hope to read in the near future. The problem is that I haven't read one book on my list in over six months. Not that I'm not reading -- I'm just not reading the books I most look forward to reading. So, lately, in order to entice myself to start hacking away at my long list, I have been buying these books and piling them up on my desk. I have decided that my "holiday" reading list is as follows:

1. Her Body Knows by David Grossman

2. Mr. Mani by A. B. Yehoshua

3. Saving Fish From Drowning by Amy Tan

4. White Teeth by Zadie Smith

5. Natasha by David Bezmozgis

6. There Are Jews In My House by Laura Vapnar

Of course it's unlikely that I will get through more than two of these, in between MLA and AJS conferences, but one can dream . . .

So, what is everyone else planning to read over the holidays?

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Tefillin Barbie

For those of you who are wondering, no I do not have Tefillin Barbie. But this is one of the strangest things I've ever seen.

Friday, October 27, 2006

Graven Images and the Law of Anti-Idolatry

An Amish couple in Pittsburgh recently filed a lawsuit (something the Amish don't typically do) against the federal government for requiring them to provide photographs for immigration purposes. (Read it) The husband, a Canadian citizen, wishes to become a permanent resident so that he ultimately can become a citizen. As a result of increasing threats of terrorism, the government has stopped making exceptions based on religion, and so the Amish husband is forced to grapple with this dilemma: provide immigration officials with a photograph of himself or risk deportation.

Why do the Amish have a problem with photographs? Because, according to their beliefs, photographs violate one of the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven images, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

Now, of course, I wish that the government could accommodate them in their beliefs, and not force them to provide photographs. But let's say the government says, "No, I'm sorry, sir, you have to provide a photograph, or we will deport you, while your wife and two children remain here, now husband and fatherless."

It seems to me that the ethical decision would be to bear down and smile for the camera -- because the alternative, deportation, inflicts great damage on other people, the family who will be left alone. It becomes a question of what is going to be more upsetting to God -- the fact that you took one photograph, or the fact that you allowed your family to be left without a father and husband?

I have seen this far too often in religious communities -- people privileging the laws and rules over the number one Commandment in both the Hebrew bible and the New Testament: Love your Neighbor. In fact, the bible is full of examples of what not to do, examples of what happens when you privilege (or idolize) a commandment over the welfare of another human being.

Take Abraham, the great Patriarch, for example. When faced with the ultimate ethical dilemma -- murder your son at the behest of a voice from heaven in order to prove your love for God, or spare the life of your child, your gift from God -- Abraham would rather listen to voices from heaven, and blindly and unquestioningly follows orders, than actually think critically about what, really, God would want him to do. Abraham idolizes a commandment over the ethical, over the life of his son. And though ultimately Abraham's son Isaac is spared (another voice from heaven stops Abraham), he is forever traumatized, and we see this play out in the dysfunction of Isaac's own family, and his sons' families. Isaac, perhaps the first poster boy for PTSD, never really gets off the sacrificial altar, never really recovers from the pain of realizing that his father could easily have killed him in order to honor an arbitrary commandment.

It's a paradigm that, in many ways, still haunts us even today. But it should be common sense: the lives of your children, and their wellbeing, should come first.

Why do the Amish have a problem with photographs? Because, according to their beliefs, photographs violate one of the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven images, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

Now, of course, I wish that the government could accommodate them in their beliefs, and not force them to provide photographs. But let's say the government says, "No, I'm sorry, sir, you have to provide a photograph, or we will deport you, while your wife and two children remain here, now husband and fatherless."

It seems to me that the ethical decision would be to bear down and smile for the camera -- because the alternative, deportation, inflicts great damage on other people, the family who will be left alone. It becomes a question of what is going to be more upsetting to God -- the fact that you took one photograph, or the fact that you allowed your family to be left without a father and husband?

I have seen this far too often in religious communities -- people privileging the laws and rules over the number one Commandment in both the Hebrew bible and the New Testament: Love your Neighbor. In fact, the bible is full of examples of what not to do, examples of what happens when you privilege (or idolize) a commandment over the welfare of another human being.

Take Abraham, the great Patriarch, for example. When faced with the ultimate ethical dilemma -- murder your son at the behest of a voice from heaven in order to prove your love for God, or spare the life of your child, your gift from God -- Abraham would rather listen to voices from heaven, and blindly and unquestioningly follows orders, than actually think critically about what, really, God would want him to do. Abraham idolizes a commandment over the ethical, over the life of his son. And though ultimately Abraham's son Isaac is spared (another voice from heaven stops Abraham), he is forever traumatized, and we see this play out in the dysfunction of Isaac's own family, and his sons' families. Isaac, perhaps the first poster boy for PTSD, never really gets off the sacrificial altar, never really recovers from the pain of realizing that his father could easily have killed him in order to honor an arbitrary commandment.

It's a paradigm that, in many ways, still haunts us even today. But it should be common sense: the lives of your children, and their wellbeing, should come first.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Phenomenology of Eros

Levinas always resonates with me, but tonight as I was finishing Totality and Infinity, I kept coming back to these passages:

"Alongside of the night as anonymous rustling of the there is extends the night of the erotic, behind the night of insomnia the night of the hidden, the clandestine, the mysterious, land of the virgin, simultaneously uncovered by Eros and refusing Eros -- another way of saying: profanation" (258).

"The caress aims at neither a person nor a thing. It loses itself in a being that dissipates as though into an impersonal dream without will and even without resistance, a passivity, an already animal or infantile anonymity, already entirely at death" (259).

"Love is not reducible to a knowledge mixed with affective elements which would open to it an unforeseen plane of being. It grasps nothing, issues in no concept, does not issue, has neither the subject-object structure nor the I-thou structure. Eros is not accomplished as a subject that fixes an object, nor as a pro-jection, toward a possible. Its movement consists in going beyond the possible" (261).

What am I most struck by? The idea of love as profanation. I suppose it feels like that sometimes, does it not? But Levinas does not really, that I can see, propose an alternative to this profanation. This is where I wish I knew more Kierkegaard. And I have another thought: you can only love the person whose face you can see. I think this is the difference between love for another person, and obsession with that same person.

This is so depressing and dark. Looks like I'm back to my old ways of looking at the world.

"Alongside of the night as anonymous rustling of the there is extends the night of the erotic, behind the night of insomnia the night of the hidden, the clandestine, the mysterious, land of the virgin, simultaneously uncovered by Eros and refusing Eros -- another way of saying: profanation" (258).

"The caress aims at neither a person nor a thing. It loses itself in a being that dissipates as though into an impersonal dream without will and even without resistance, a passivity, an already animal or infantile anonymity, already entirely at death" (259).

"Love is not reducible to a knowledge mixed with affective elements which would open to it an unforeseen plane of being. It grasps nothing, issues in no concept, does not issue, has neither the subject-object structure nor the I-thou structure. Eros is not accomplished as a subject that fixes an object, nor as a pro-jection, toward a possible. Its movement consists in going beyond the possible" (261).

What am I most struck by? The idea of love as profanation. I suppose it feels like that sometimes, does it not? But Levinas does not really, that I can see, propose an alternative to this profanation. This is where I wish I knew more Kierkegaard. And I have another thought: you can only love the person whose face you can see. I think this is the difference between love for another person, and obsession with that same person.

This is so depressing and dark. Looks like I'm back to my old ways of looking at the world.

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Friday, September 29, 2006

Religion of Eternal Childhood

In re-reading part of Sandor Goodhart's Sacrificing Commentary tonight, I'm led to wonder how much our individual (and collective) ideas about God, and who God is and what he is capable of, are governed by our own personalities -- our own sets of needs and desires. In other words, to what extent do we, knowingly or not, construct our understanding of God based on what it is we long for, or what we have seen fail in our own lives?

In the chapter "The Holocaust, Witness, and Responsibility," Goodhart juxtaposes two texts (by Emmanuel Levinas and Halpern Leivick) and ultimately concludes that:

"In the wake of an experience like that of the Holocaust, atheism or the death of God might seem the most natural (perhaps even the most reasonable) response. But we make that response only if we have held up until this moment a particularly childlike conception of God -- of one who inflicts injury and awards prizes, a God, that is to say, of eternal children. On the other hand, if we expand our conception of transcendence, if we allow God at least the same sophistication we grant ourselves, alternative possibilities appear. His very absence, for example, may be taken less as a sign of abandonment than as an index of our own responsibility for (and implication in) human behavior" (238).

To give you some context, Leivick (Yiddish poet and playwright) laments that, unlike in the biblical binding of Isaac, when it came to the Holocaust, the angel of God came too late, was tardy. Levinas, however, as you can guess, "offers us a way of distinguishing a religion of adults from a religion of eternal childhood" through the face-to-face encounter. In remarking upon the suffering of innocents, Levinas says:

"Does it not bear witness to a world that is without God, to a land where man alone measures Good and Evil? The simplest and most common response to this question would lead to atheism. This is no doubt also the sanest reaction for all those for whom up until a moment ago a God, conceived a bit primitively, distributed prizes, inflicted sanctions, or pardoned faults, and in His kindness treated human beings as eternal children. "

And, my favorite lines: "But with what narrow-minded demon, with what strange magician did you thus populate your sky, you who now declare it to be deserted? And why under such an empty sky do you continue to seek a world that is meaningful and good?" (237).

In the chapter "The Holocaust, Witness, and Responsibility," Goodhart juxtaposes two texts (by Emmanuel Levinas and Halpern Leivick) and ultimately concludes that:

"In the wake of an experience like that of the Holocaust, atheism or the death of God might seem the most natural (perhaps even the most reasonable) response. But we make that response only if we have held up until this moment a particularly childlike conception of God -- of one who inflicts injury and awards prizes, a God, that is to say, of eternal children. On the other hand, if we expand our conception of transcendence, if we allow God at least the same sophistication we grant ourselves, alternative possibilities appear. His very absence, for example, may be taken less as a sign of abandonment than as an index of our own responsibility for (and implication in) human behavior" (238).

To give you some context, Leivick (Yiddish poet and playwright) laments that, unlike in the biblical binding of Isaac, when it came to the Holocaust, the angel of God came too late, was tardy. Levinas, however, as you can guess, "offers us a way of distinguishing a religion of adults from a religion of eternal childhood" through the face-to-face encounter. In remarking upon the suffering of innocents, Levinas says:

"Does it not bear witness to a world that is without God, to a land where man alone measures Good and Evil? The simplest and most common response to this question would lead to atheism. This is no doubt also the sanest reaction for all those for whom up until a moment ago a God, conceived a bit primitively, distributed prizes, inflicted sanctions, or pardoned faults, and in His kindness treated human beings as eternal children. "

And, my favorite lines: "But with what narrow-minded demon, with what strange magician did you thus populate your sky, you who now declare it to be deserted? And why under such an empty sky do you continue to seek a world that is meaningful and good?" (237).

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Boxed in By Jesus

My internet service has been down since yesterday evening, and so I have had to seek out "hot spots" in my house where I can "borrow" my neighbors' signals, or wander down to the library or a coffee shop that offers wireless. It's gloomy outside today, and about an hour ago, as I walked from coffee shop to coffee shop, trying to find one that isn't filled with noisy undergraduates or annoying musicians, I was accosted by a man wearing a box around his body that said: "The Lord has made his salvation known to men." As he and his other box-wearing (each with a different verse) friends made one large box of their own and closed in around me, the original one very kindly tried to hand me a tract. He looked at me so sadly, but sweetly, as if I was the most dejected human being on the planet, and asked, "Do you know Jesus?"

"None of us here know Jesus, including you," I responded, to my own surprise, "or we would all be out feeding the poor or volunteering in medical clinics." I'm not sure where this came from, but I think I must believe it on some level. And I was able to squeeze through the little chink I had created in the wall of box-wearers and slide into the next coffee shop. I think I hurt his feelings, though I didn't mean to; he was very sweet and sincere. But street witnessing doesn't work, and at any rate, the box outfit is not a good look for anyone. I wish I had a camera phone.

"None of us here know Jesus, including you," I responded, to my own surprise, "or we would all be out feeding the poor or volunteering in medical clinics." I'm not sure where this came from, but I think I must believe it on some level. And I was able to squeeze through the little chink I had created in the wall of box-wearers and slide into the next coffee shop. I think I hurt his feelings, though I didn't mean to; he was very sweet and sincere. But street witnessing doesn't work, and at any rate, the box outfit is not a good look for anyone. I wish I had a camera phone.

L'Shana Tova

I'm spending Rosh Hashanah alone this year, for the first time in quite a while, while others celebrate with their "families." I suppose I'm not Jewish enough for some people, and not Christian enough for others. A lonely place, indeed. I feel like a hyphen, a very long and sharply pronounced hyphen.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Reading Nathanael West

From The Day of the Locust:

"It's hard to laugh at the need for beauty and romance, no matter how tasteless, even horrible, the results of that are. But it is easy to sigh. Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous" (24).

"It's hard to laugh at the need for beauty and romance, no matter how tasteless, even horrible, the results of that are. But it is easy to sigh. Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous" (24).

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

The Death of Reading, Deferred

After emailing the writer of the piece I blogged below, I received this email today, and I feel a bit better, though I think that, if it was truly intended to be a satire it could have been done more effectively. But at least I'm one of the people who got "extra points" for asking him whether it was something along the lines of "A Modest Proposal"!

Dear Practical Futurist reader,

I prefer to correspond with my readers more personally, but I received so much email on the “Worth of Reading” column that I must resort to a group mailing.

As a writer, I deeply appreciate how many of you came to the defense of reading—even if it involved some fairly harsh words aimed at me. But I need to point out that the dateline on the article was December 25, 2025.

In other words, the entire piece was written as a commentary from the future, so the story is fictional, depicting an outcome and attitude that as a writer I dearly hope doesn't transpire (but sometimes fear we may be heading toward).

I've received more than 500 emails on this column, about 80% horrified by "my" attitude. The other 20% of the readers recognized that the piece was hypothetical and satirical, set in 2025 (and they got extra points if they mentioned a conceptual similarity to Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal.”) Distressingly, those were also the readers who agreed that if American literacy, especially among the young, continues on its current course, the dreadful outcome I imagined might not be far from the truth.

Let’s hope not! Here’s to many more decades of happy and fluent readers yet to come—

Michael R.

Michael Rogers

http://www.practicalfuturist.com/

on MSNBC.com

Dear Practical Futurist reader,

I prefer to correspond with my readers more personally, but I received so much email on the “Worth of Reading” column that I must resort to a group mailing.

As a writer, I deeply appreciate how many of you came to the defense of reading—even if it involved some fairly harsh words aimed at me. But I need to point out that the dateline on the article was December 25, 2025.

In other words, the entire piece was written as a commentary from the future, so the story is fictional, depicting an outcome and attitude that as a writer I dearly hope doesn't transpire (but sometimes fear we may be heading toward).

I've received more than 500 emails on this column, about 80% horrified by "my" attitude. The other 20% of the readers recognized that the piece was hypothetical and satirical, set in 2025 (and they got extra points if they mentioned a conceptual similarity to Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal.”) Distressingly, those were also the readers who agreed that if American literacy, especially among the young, continues on its current course, the dreadful outcome I imagined might not be far from the truth.

Let’s hope not! Here’s to many more decades of happy and fluent readers yet to come—

Michael R.

Michael Rogers

http://www.practicalfuturist.com/

on MSNBC.com

Monday, September 18, 2006

The Worth of Words

I just read one of the most disturbing things ever -- a case against the significance of reading, and in support of reading literacy going by the wayside over the next two decades. Please, someone, tell me whether this is satire -- something along the lines of Swift's "A Modest Proposal," though not nearly as well done -- or whether this is real.

Strangely, I'm much more comfortable contemplating my own eventual physical death than I am pondering the possibility of the twin deaths of literature and reading.

Strangely, I'm much more comfortable contemplating my own eventual physical death than I am pondering the possibility of the twin deaths of literature and reading.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Rabbis Ordained in Germany

Today, in Germany, the first rabbi was ordained since 1942.

"After the Holocaust, many people could never have imagined that Jewish life in Germany could blossom again," said German President Horst Koehler before the event. "That is why the first ordination of rabbis in Germany is a very special event indeed."

Read about it in the Washington Post.

"After the Holocaust, many people could never have imagined that Jewish life in Germany could blossom again," said German President Horst Koehler before the event. "That is why the first ordination of rabbis in Germany is a very special event indeed."

Read about it in the Washington Post.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

For All Eyes Only

In the New York Times this morning you can read some of Susan Sontag's journal entries, and though it felt a bit weird to be reading what someone has presumably written to herself, Sontag herself claims that journals are written "precisely to be read furtively by other people." I'm not sure I agree with that, but it made me feel better as I read on.

A couple things I liked or found interesting:

"The fear of becoming old is born of the recognition that one is not living now the life that one wishes. It is equivalent to a sense of abusing the present." Now that rings true -- how else can I explain what I experience as my impending doom (turning 30 next year)?

"It’s corrupting to write with the intent to moralize, to elevate people’s moral standards." Not entirely sure I agree with this, but it's interesting to consider.

"A freshly typed manuscript, the moment it’s completed, begins to stink. It’s a dead body — it must be buried — embalmed, in print."

A couple things I liked or found interesting:

"The fear of becoming old is born of the recognition that one is not living now the life that one wishes. It is equivalent to a sense of abusing the present." Now that rings true -- how else can I explain what I experience as my impending doom (turning 30 next year)?

"It’s corrupting to write with the intent to moralize, to elevate people’s moral standards." Not entirely sure I agree with this, but it's interesting to consider.

"A freshly typed manuscript, the moment it’s completed, begins to stink. It’s a dead body — it must be buried — embalmed, in print."

Monday, September 04, 2006

Broken World

"Holiness is not a competition, but a call to everyone to transcend self-absorption and participate in the healing of our broken world."

I read this line this morning in a letter from a Catholic nun to the New York Times. Sounds a lot like tikkun olam. How nice it would be if this concept, which is in theory at the heart of both Judaism and Christianity (Protestantism and Catholocism), was all we needed.

I read this line this morning in a letter from a Catholic nun to the New York Times. Sounds a lot like tikkun olam. How nice it would be if this concept, which is in theory at the heart of both Judaism and Christianity (Protestantism and Catholocism), was all we needed.

Saturday, September 02, 2006

The Devil Made Me Do It

As a fervent lover of the Hebrew bible, and speaking from a long history of exposure to Christianity, I have always had an ambivalent relationship with the New Testament's Paul. But in some instances, I have to admit that he gets at the complexity of being human:

"For that which I do I allow not: for what I would, that do I not; but what I hate, that do I" (Rom. 7:15).

Considering how frustrated I am with myself from time to time, I thought of this verse this morning and searched for it. I can relate with this verse. But then it gets a bit out of the realm of what I consider acceptable:

"Now then it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me. For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh) dwelleth no good thing: for to willis present with me; but how to perform that which is good I find not . . . Now if I do that I would not, it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me" (Rom 7:17-18, 20).

I know what Paul is getting at, but my fear is that it opens up a space in which people can too easily place blame on somebody, or something, else -- to say, metaphorically speaking, "the devil made me do it." Though I would love to blame "the devil" for many of my actions, I fear that I am always already responsible for them.

I suppose, though, that this is a valiant effort on Paul's part to explore the complexity of being human, and the potential for conflicting emotions and desires.

"For that which I do I allow not: for what I would, that do I not; but what I hate, that do I" (Rom. 7:15).

Considering how frustrated I am with myself from time to time, I thought of this verse this morning and searched for it. I can relate with this verse. But then it gets a bit out of the realm of what I consider acceptable:

"Now then it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me. For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh) dwelleth no good thing: for to willis present with me; but how to perform that which is good I find not . . . Now if I do that I would not, it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me" (Rom 7:17-18, 20).

I know what Paul is getting at, but my fear is that it opens up a space in which people can too easily place blame on somebody, or something, else -- to say, metaphorically speaking, "the devil made me do it." Though I would love to blame "the devil" for many of my actions, I fear that I am always already responsible for them.

I suppose, though, that this is a valiant effort on Paul's part to explore the complexity of being human, and the potential for conflicting emotions and desires.

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Levinas and Poe's Raven

I'm sitting in on an Emmanuel Levinas class this semester, simply for personal edification. And in reading his Existence and Existents (written while he was a prisoner of war) for the first time, I'm amazed at how largely the concept of the "there is" figures into Levinas's early, pre-Totality and Infinity work. There is not, however, any trace of what will become the fundamentally Levinasian notion of the face-to-face. But it's filled with literary references and illusions -- Rimbaud, Shakespeare, Racine, Baudelaire, Homer, Blanchot -- that, for me, ground an otherwise dense work. One subtle reference to Edgar Allen Poe is particularly intriguing, and must have been personally resonant for Levinas, as he sat as a prisoner of war:

"If death is nothingness, it is not nothingness pure and simple; it still has the reality of a chance that was lost. The 'nevermore' hovers about like a raven in the dismal night, like a reality in nothingness. The incompleteness of this evanescence is manifest in the regret which accompanies it. . . " (77).

Even death, it seems, for Levinas, is too nuanced to be simply "nothingness."

"If death is nothingness, it is not nothingness pure and simple; it still has the reality of a chance that was lost. The 'nevermore' hovers about like a raven in the dismal night, like a reality in nothingness. The incompleteness of this evanescence is manifest in the regret which accompanies it. . . " (77).

Even death, it seems, for Levinas, is too nuanced to be simply "nothingness."

Monday, August 21, 2006

Dining With Hitler

I just read a short article about a new restaurant that opened in India called Hitler's Cross, named after Adolf Hitler and promoted with posters showing the German leader and Nazi swastikas. India's small Jewish community, of course, is outraged.

“This place is not about wars or crimes, but where people come to relax and enjoy a meal,” said restaurant manager Fatima Kabani, adding that they were planning to turn the eatery’s name into a brand with more branches in Mumbai.

“We wanted to be different. This is one name that will stay in people’s minds,” owner Punit Shablok told Reuters. “We are not promoting Hitler. But we want to tell people we are different in the way he was different.” Different? Not the word I would use to describe Hitler, or this restaurant.

Now, seriously. I can't even comment on this creepy brand of anti-Semitism.

“This place is not about wars or crimes, but where people come to relax and enjoy a meal,” said restaurant manager Fatima Kabani, adding that they were planning to turn the eatery’s name into a brand with more branches in Mumbai.

“We wanted to be different. This is one name that will stay in people’s minds,” owner Punit Shablok told Reuters. “We are not promoting Hitler. But we want to tell people we are different in the way he was different.” Different? Not the word I would use to describe Hitler, or this restaurant.

Now, seriously. I can't even comment on this creepy brand of anti-Semitism.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

The Corruptibility of Günter Grass

Today's New York Times has two op-ed pieces on the unfortunate revelation of Günter Grass's sordid Nazi background: Daniel Kehlmann's "A Prisoner of the Nobel" and Peter Gay's "The Fictions of Günter Grass." As if being any kind of Nazi isn't bad enough, Grass was apparently part of the Waffen SS, who played a particularly ugly role in the Holocaust. Kehlmann's piece raises an interesting point:

"His participation in Hitler’s elite corps could have been seen as youthful foolishness, but his silence over so many years is another matter. And naturally, there are consequences for Germany’s image in the world. When even the most outspoken German moralist wore the uniform of murderers, one might ask whether there is a single guiltless German in this generation."

In the world of Levinasian ethics one might say that Grass is doubly responsible for his role in the Holocaust: first for the direct action, and second for his concealment of that action -- the concealment of the action continues and extends it, perpetuates its legacy. Both articles point out that had Grass come forward about his past in 1959 after the publication of The Tin Drum, perhaps he could now retain some of his well-deserved literary respect. But clearly we will never view Grass, newly Nobel prize-less, in the same way.

"His participation in Hitler’s elite corps could have been seen as youthful foolishness, but his silence over so many years is another matter. And naturally, there are consequences for Germany’s image in the world. When even the most outspoken German moralist wore the uniform of murderers, one might ask whether there is a single guiltless German in this generation."

In the world of Levinasian ethics one might say that Grass is doubly responsible for his role in the Holocaust: first for the direct action, and second for his concealment of that action -- the concealment of the action continues and extends it, perpetuates its legacy. Both articles point out that had Grass come forward about his past in 1959 after the publication of The Tin Drum, perhaps he could now retain some of his well-deserved literary respect. But clearly we will never view Grass, newly Nobel prize-less, in the same way.

Monday, August 14, 2006

Learning About the Holocaust in Iran

Today the Holocaust cartoon exhibit opened in Tehran, Iran. I still haven't figured out how this is an acceptable response to the Danish cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad nearly a year ago. Apparently 50 people attended the exhibit today, and one 23-year-old woman remarked: "I came to learn more about the roots of the Holocaust and the basis of Israel's emergence."

I nearly choked on a piece of candy I was eating when I read that. Since when can one learn anything truthful about Israel, Jews, or the Holocaust in an Islamic country, particularly one whose president has essentially called the Holocaust a fiction? It would be like going to the Duke Lacrosse team for lesson on diversity and how to treat women.

I nearly choked on a piece of candy I was eating when I read that. Since when can one learn anything truthful about Israel, Jews, or the Holocaust in an Islamic country, particularly one whose president has essentially called the Holocaust a fiction? It would be like going to the Duke Lacrosse team for lesson on diversity and how to treat women.

Friday, August 11, 2006

The Rhetoric of Denim

I knew that denim had a scholarly purpose. This looks like an interesting read.

Sunday, August 06, 2006

Busy Times

I'm sorry that there has been no action around here lately. I'm still in the process of moving, and planning my syllabus, and studying Italian, and . . . but I'll be back soon.

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Spinoza and Doubt

Today Rebecca Goldstein has an interesting op-ed essay ("Reasonable Doubt") in the New York Times. It is partially in commemoration of the "350th anniversary of the excommunication of the philosopher Baruch Spinoza from the Portuguese Jewish community of Amsterdam in which he had been raised." The essay brings Spinoza's life and thought into the context of today's (this past week's) international events. It's a good essay.

But it also occurs to me that nothing, or at least very little, is "true" beyond "reasonable doubt." My ideas about God and religion, as unwaveringly right as they might feel to me, are still susceptible to the voice of reason. I'm not sure whether this is a scary or liberating concept.

But it also occurs to me that nothing, or at least very little, is "true" beyond "reasonable doubt." My ideas about God and religion, as unwaveringly right as they might feel to me, are still susceptible to the voice of reason. I'm not sure whether this is a scary or liberating concept.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Not Christian, Jew, or Muslim

This video clip from Al-Jazeera is stunning, though I fear that this woman is going to need some serious protection from the world of Islamic fundamentalism. After watching this video the prospect of secularism as opposed to monotheism is inviting.

You must watch this video.

You must watch this video.

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

The Temptation of Violence

I've come to realize that what concerns me most -- and inevitably hovers over my dissertation and all other academic scholarship -- are theological questions. Like most people, I want answers. But unlike many people, I've grown more content with the knowledge that often the "answer" is merely one more explosion of unanswerable questions and unsolvable conundrums. And yet, driven by an intellectual era dominated by postsecular concerns, I still work, study, read, and write in a "find the answer" mode. Perhaps this is one reason I am so drawn to Judaism (perhaps instead I should say Jewish thought, or even Jewish ethical monotheism) -- the insistence that the experience of working toward or looking for "answers" is more significant than what we actually hope to find as a result of our inquisitive endeavors. It is a dynamic ethical system, capable of continually and subtly evolving past what others conceive of as an outdated, monolithic set of rules and guidelines.

Tonight in particular I was thinking about the ways that some people use biblical principles and scriptures to indirectly insult, and essentially assault, others. The bible has become a weapon of sorts -- a sword brandished high above the heads of those who fear that their own theological foundations are too shaky to allow for the inclusion of those who don't believe exactly as they do. Ironically, however, when I was young I remember sitting in Sunday school (I was raised in a very conservative Christian home and community), and being told that I should put on the full armor of God, and that the bible was my sword (this metaphorical rendering comes from Paul's letter to the Ephesians). We even engaged in little contests that were called Sword Drills, in which we would race to see who could look up a scripture verse first. Is it any wonder that so many people are conditioned to utilize the bible and its contents and interpretations as if it is indeed a deadly weapon? But despite the seeming rhetoric of violence, the New Testament writers (one in particular) admonish people to live peaceably with one another.

I am not in any way saying that there are not truths to be found in the Christian New Testament --- quite the contrary. The world would be a wonderful place if all Christians were Christ-like. I just find the violent imagery and metaphors fascinating, especially in the wake of such a hideous historical misuse of the bible.

One of my younger brothers was especially shrewd when it came to strategically using the bible as a "weapon." When he was in fifth or sixth grade, he perused the New Testament for any verses that could be construed to be anti-women or mysogynist (there are quite a few, to be sure, particularly in the Pauline epistles), and then he wrote them all down on tiny scraps of paper, which he kept in the pockets of his Levi's jeans. There was another little girl from our church who apparently annoyed him, and so when she pushed him too far, he would whip out the scraps of paper and unleash a slew of biblically charged insults. A hilarious family anecdote, to be sure, but it's somewhat disturbing.

Likewise, it was not uncommon among people in the Christian college community in which I lived during my undergraduate years to hurl scriptures at people in disagreements as a way to hurt or somehow incriminate the other person. These were also more often than not the most vicious and hypocritical people.

And now, tonight, I'm again looking at Emmanuel Levinas's "The Temptation of Temptation," in which he recalls the Talmudic story (Tractate Shabbath) of a Sadducee who came upon Raba, who was so buried in Torah study, that as he sat absentmindedly rubbing his heel, blood began to spurt from it. This story is the starting point for my dissertation, and I never cease to be fascinated by its implications, primarily that Torah study (or bible or any other text, I would argue) is always accompanied by a necessary violence -- that the violence is necessary in order to wrest from the text the meaning that is concealed. I also can't help but think of Rene Girard's Violence and the Sacred here.

There's no way out of violence, it seems, and this imperative becomes even more profound in the context of spiritual and theological inquiry.

Tonight in particular I was thinking about the ways that some people use biblical principles and scriptures to indirectly insult, and essentially assault, others. The bible has become a weapon of sorts -- a sword brandished high above the heads of those who fear that their own theological foundations are too shaky to allow for the inclusion of those who don't believe exactly as they do. Ironically, however, when I was young I remember sitting in Sunday school (I was raised in a very conservative Christian home and community), and being told that I should put on the full armor of God, and that the bible was my sword (this metaphorical rendering comes from Paul's letter to the Ephesians). We even engaged in little contests that were called Sword Drills, in which we would race to see who could look up a scripture verse first. Is it any wonder that so many people are conditioned to utilize the bible and its contents and interpretations as if it is indeed a deadly weapon? But despite the seeming rhetoric of violence, the New Testament writers (one in particular) admonish people to live peaceably with one another.

I am not in any way saying that there are not truths to be found in the Christian New Testament --- quite the contrary. The world would be a wonderful place if all Christians were Christ-like. I just find the violent imagery and metaphors fascinating, especially in the wake of such a hideous historical misuse of the bible.

One of my younger brothers was especially shrewd when it came to strategically using the bible as a "weapon." When he was in fifth or sixth grade, he perused the New Testament for any verses that could be construed to be anti-women or mysogynist (there are quite a few, to be sure, particularly in the Pauline epistles), and then he wrote them all down on tiny scraps of paper, which he kept in the pockets of his Levi's jeans. There was another little girl from our church who apparently annoyed him, and so when she pushed him too far, he would whip out the scraps of paper and unleash a slew of biblically charged insults. A hilarious family anecdote, to be sure, but it's somewhat disturbing.

Likewise, it was not uncommon among people in the Christian college community in which I lived during my undergraduate years to hurl scriptures at people in disagreements as a way to hurt or somehow incriminate the other person. These were also more often than not the most vicious and hypocritical people.

And now, tonight, I'm again looking at Emmanuel Levinas's "The Temptation of Temptation," in which he recalls the Talmudic story (Tractate Shabbath) of a Sadducee who came upon Raba, who was so buried in Torah study, that as he sat absentmindedly rubbing his heel, blood began to spurt from it. This story is the starting point for my dissertation, and I never cease to be fascinated by its implications, primarily that Torah study (or bible or any other text, I would argue) is always accompanied by a necessary violence -- that the violence is necessary in order to wrest from the text the meaning that is concealed. I also can't help but think of Rene Girard's Violence and the Sacred here.

There's no way out of violence, it seems, and this imperative becomes even more profound in the context of spiritual and theological inquiry.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

I Could Be A Physician By Now, Right?

I just had a great big laugh. Yesterday I emailed an old girlfriend from college. Although we haven't spoken for years (a falling out of sorts), we used to be quite good friends, and so I thought it would be nice to send her a brief note to say hello. In my letter, I wrote that I was still in Indiana, but almost finished with my PhD. I remarked on the cold winters here. Then I wished her well, and told her I would love to hear what's going on in her life.

Her surprising reply (in part) reads as follows:

"Oh my gosh, Mon! You're in Indiana? And still in school?? I can't even begin to comprehend how much time you've spent in classes - you realize you could be a physician by now, right? You're probably either crazy or highly intelligent (likely the latter) . . . oh, and we live right by South Coast Plaza [Orange County, California] which I can report has absolutely lovely winters. And summers, and springs, so try to get hired on the west coast if at all possible. Hey... I'll bet Victorville Community College is hiring! Yes, it's perfect."

Now, first of all, why is it that some people still conceive of an MD as the most prestigious degree? Why should it matter that I could have been a physician by now? Wouldn't I have done that if I had been so inclined? It is as if she is saying, "What a shame you won't have anything better to show for all these years of classes other than a silly little PhD!" And, while I am indeed both "crazy" and presumably "highly intelligent," it's clear that she wants me to know that she believes the former alone is true. And, Victorville Community College is a notoriously bad community college near my home town of Apple Valley, California (though I did take a phenomenal history class there one summer).

So, my question is, then, when did getting a PhD in English become such a waste of time?

Her surprising reply (in part) reads as follows:

"Oh my gosh, Mon! You're in Indiana? And still in school?? I can't even begin to comprehend how much time you've spent in classes - you realize you could be a physician by now, right? You're probably either crazy or highly intelligent (likely the latter) . . . oh, and we live right by South Coast Plaza [Orange County, California] which I can report has absolutely lovely winters. And summers, and springs, so try to get hired on the west coast if at all possible. Hey... I'll bet Victorville Community College is hiring! Yes, it's perfect."

Now, first of all, why is it that some people still conceive of an MD as the most prestigious degree? Why should it matter that I could have been a physician by now? Wouldn't I have done that if I had been so inclined? It is as if she is saying, "What a shame you won't have anything better to show for all these years of classes other than a silly little PhD!" And, while I am indeed both "crazy" and presumably "highly intelligent," it's clear that she wants me to know that she believes the former alone is true. And, Victorville Community College is a notoriously bad community college near my home town of Apple Valley, California (though I did take a phenomenal history class there one summer).

So, my question is, then, when did getting a PhD in English become such a waste of time?

Sunday, July 09, 2006

Home is Where the Struggles Are

Today I'm finishing a review of Janet Burstein's Telling the Little Secrets: American Jewish Writing Since the 1980s. Burstein is a really great writer, particularly for an "academic": the writing is never purposely dense or convoluted, and though it is critical writing, it is always brilliantly imaginative. Her discussion of Aryeh Lev Stollman's The Far Euphrates is especially interesting. The novel is the story of a young Jewish/Canadian boy named Alexander, who tries to recapture the ambiguous and painful memories of his childhood. The distance, loss, and separation that he associates with "home" subtly evoke the consequences of inhabiting a post-Holocaust world, particularly for a Jewish family.

But I am intrigued by Burstein's suggestion that "from the womb onward, home may be the site of our most desperate struggles -- a struggle first to receive nurture and care, then to achieve independence, and finally to assume responsibility" (108). It gives new meaning to the phrase "dysfunctional family." Dysfunction is perhaps only a symptom of home.

Now I'm going to read a bit into that quotation. In my family, as in my own life, it seems like there is always some kind of drama. Whether it's me getting into two car accidents in one month, my dad walking outside and being bitten by a deadly snake, my brothers being literally jumped by a Samoan gang, or an overly heated family debate over politics in the kitchen, there always seems to be a struggle or conflict of some sort. I've often asked myself why this is -- why our household is more action-packed than most. I have typically perceived of it as a negative (though perhaps beyond our control) phenomenon, but now I'm not so sure. I wonder if it is the existence of struggle or conflict that brings us together, makes us strong. I like Burstein's idea of home as the "site of our most desperate struggles" because it allows me to conceive of my family's predicament from a different, and more promising, perspective: my own personal family life may be full of struggles, but perhaps it's just that we know what it means to be "home," and we're comfortable being there in what it is.

But I am intrigued by Burstein's suggestion that "from the womb onward, home may be the site of our most desperate struggles -- a struggle first to receive nurture and care, then to achieve independence, and finally to assume responsibility" (108). It gives new meaning to the phrase "dysfunctional family." Dysfunction is perhaps only a symptom of home.

Now I'm going to read a bit into that quotation. In my family, as in my own life, it seems like there is always some kind of drama. Whether it's me getting into two car accidents in one month, my dad walking outside and being bitten by a deadly snake, my brothers being literally jumped by a Samoan gang, or an overly heated family debate over politics in the kitchen, there always seems to be a struggle or conflict of some sort. I've often asked myself why this is -- why our household is more action-packed than most. I have typically perceived of it as a negative (though perhaps beyond our control) phenomenon, but now I'm not so sure. I wonder if it is the existence of struggle or conflict that brings us together, makes us strong. I like Burstein's idea of home as the "site of our most desperate struggles" because it allows me to conceive of my family's predicament from a different, and more promising, perspective: my own personal family life may be full of struggles, but perhaps it's just that we know what it means to be "home," and we're comfortable being there in what it is.

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

I am an American

This is it -- proof that I forced myself to emerge from my dungeon today, long enough to wear a patriotic color, go to a bbq, watch people drink beer, discuss flag-burning, pretend to be happy, and eat apple pie. Today I am an American, of sorts, apparently. But now I'm back in my lair, hiding out while everyone else watches fireworks. There was only so much celebration that I could take.

Monday, July 03, 2006

A Warning Against Sun-tanning

I'm just about finished with Margaret Atwood's The Blind Assassin. It's taken me forever since I keep stopping to read other things. But I came across something very useful today.

The main character notices that her doctor is beginning to age: "...the shoe of aging is beginning to pinch," she says to herself, "Soon you'll regret all that sun-tanning. Your face will look like a testicle."

One of my loved ones is constantly imploring me to use sunscreen. I never, or rarely, listen. Perhaps if I had been told that my face would one day look like a testicle, I would have put on sunscreen. Everyday. Even in the winter. It's not a good look -- for anyone.

The main character notices that her doctor is beginning to age: "...the shoe of aging is beginning to pinch," she says to herself, "Soon you'll regret all that sun-tanning. Your face will look like a testicle."

One of my loved ones is constantly imploring me to use sunscreen. I never, or rarely, listen. Perhaps if I had been told that my face would one day look like a testicle, I would have put on sunscreen. Everyday. Even in the winter. It's not a good look -- for anyone.

Sunday, June 25, 2006

"La memoria dell' offesa" ("The Memory of the Offense")

As if my life isn't already filled with things to take time away from my dissertation writing, I'm faced with the task of mastering the Italian language this summer -- or, at least, mastering it enough to pass a translation exam so that I can defend my dissertation two semesters from now. My exam will ask me to translate a couple of pages from Primo Levi's I sommersi e i salvati (The Drowned and the Saved). Though I'm not quite ready to do it in respectable form, I can figure it out for the most part, though perhaps that's because I've read the book in English. I'm sneaky like that.

I've just been looking at one chapter of the book ("The Memory of the Offense"), and the first line reads as follows:

La memoria umana è uno strumento meraviglioso ma fallace [Human memory is a marvelous but fallacious instrument].

It's an interesting statement considering the fact that Levi was, among other things, a memoirist -- a recorder of history via the "fallacious" vehicle of memory. It is of course, in my mind, a strategic move on the part of Levi because it asserts the necessity of filling in factual and "historical" gaps with feelings and perceptions, which are possibly more "real" than what we might call a factual account of a historical event. What I mean to say is that historical events are important for many reasons, but not the least of which are the ways they change how people think and feel, the ways in which they provoke human complexity to rear its complicated head. Granted, the fact that memories are not carved in stone (as Levi goes on to suggest) does not negate the harsh truth of historical realities such as the Holocaust, nor does it lessen the death blows of the fires of Auschwitz. I think the important thing inherent in Levi's statement is the underlying assertion that memory matters, if only because it connects us to our feelings, drives, passions, longings, and fears -- essentially to what makes us human.

For example, my mother and I argue constantly over events that I remember solidly from my childhood. She claims not that what I describe never happened, but that it happened nothing like how I remember it. How can this be? Likewise, someone very close to me used to say to me when I was angry or upset -- perhaps overreacting in many instances -- and trying to convey what I felt, "Your feelings are wrong!" But can feelings really be "wrong"? Is that possible?

I've just been looking at one chapter of the book ("The Memory of the Offense"), and the first line reads as follows:

La memoria umana è uno strumento meraviglioso ma fallace [Human memory is a marvelous but fallacious instrument].

It's an interesting statement considering the fact that Levi was, among other things, a memoirist -- a recorder of history via the "fallacious" vehicle of memory. It is of course, in my mind, a strategic move on the part of Levi because it asserts the necessity of filling in factual and "historical" gaps with feelings and perceptions, which are possibly more "real" than what we might call a factual account of a historical event. What I mean to say is that historical events are important for many reasons, but not the least of which are the ways they change how people think and feel, the ways in which they provoke human complexity to rear its complicated head. Granted, the fact that memories are not carved in stone (as Levi goes on to suggest) does not negate the harsh truth of historical realities such as the Holocaust, nor does it lessen the death blows of the fires of Auschwitz. I think the important thing inherent in Levi's statement is the underlying assertion that memory matters, if only because it connects us to our feelings, drives, passions, longings, and fears -- essentially to what makes us human.

For example, my mother and I argue constantly over events that I remember solidly from my childhood. She claims not that what I describe never happened, but that it happened nothing like how I remember it. How can this be? Likewise, someone very close to me used to say to me when I was angry or upset -- perhaps overreacting in many instances -- and trying to convey what I felt, "Your feelings are wrong!" But can feelings really be "wrong"? Is that possible?

Monday, June 19, 2006

God is Gray

An interesting perspective of God. I grew up in a household and religious community in which everything was black or white -- either one extreme, or another. No in-between. No middle ground. No compromising. Compromise was the dirty c-word. My way or the highway.

The rhetoric of exclusion, rather than the message of truth, it seems.

But I also think that sometimes things would be simpler if they were indeed black or white -- if right and wrong were really two distinct polarities. How much more peaceful life would be if everything didn't merge into a murky gray film. But such is life, and it's the grayness of life that keeps us alive, I think -- that ensures that we remain in dialogue, and that we have differences.

Who can blame people for trying to simplify their lives? I can't. I could use a little dose of black and white sometimes myself.

The rhetoric of exclusion, rather than the message of truth, it seems.

But I also think that sometimes things would be simpler if they were indeed black or white -- if right and wrong were really two distinct polarities. How much more peaceful life would be if everything didn't merge into a murky gray film. But such is life, and it's the grayness of life that keeps us alive, I think -- that ensures that we remain in dialogue, and that we have differences.

Who can blame people for trying to simplify their lives? I can't. I could use a little dose of black and white sometimes myself.

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Great American Books, Take Two

Okay, so after many helpful suggestions, here is my almost final, almost official list of Great American Books for the fall semester:

Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Melville: Moby Dick

West: The Day of the Locust

Heller: Catch-22

Malamud: The Natural

Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury

Morrison: Beloved

Doctorow: Ragtime

Hijuelos: Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love

Roth: American Pastoral

Still thinking about:

Kesey: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

Roth (Henry): Call It Sleep

I just realized, however, that there is only one female author on this list. Is that a problem? It might very well be. I'm a pathetic excuse for a feminist.

Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Melville: Moby Dick

West: The Day of the Locust

Heller: Catch-22

Malamud: The Natural

Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury

Morrison: Beloved

Doctorow: Ragtime

Hijuelos: Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love

Roth: American Pastoral

Still thinking about:

Kesey: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

Roth (Henry): Call It Sleep

I just realized, however, that there is only one female author on this list. Is that a problem? It might very well be. I'm a pathetic excuse for a feminist.

Saturday, June 10, 2006

Of God Who Bursts Like A Balloon

One of the novels I'm still trying to get through is Margaret Atwood's The Blind Assassin -- not that it's tough to get through (it's excellent). I'm just doing too many other things to commit lovingly to it. But the other night I stumbled on a great couple of lines, and an insightfully provocative image:

"Over the trenches God had burst like a balloon, and there was nothing left of him but grubby little scraps of hypocrisy. Religion was just a stick to beat the soldiers with, and anyone who declared otherwise was full of pious drivel" (77).

This is the narrator's description of how World War I had transformed her father into an atheist. It occurs to me, however, that this is not the first time, nor the last, that God would "burst like a balloon." Certainly the next World War brought with it repeating images of a god who bursts in the face of his people, over and over again. And it seems that he continues to burst even today, despite our continued efforts to inflate and re-inflate him.

"Over the trenches God had burst like a balloon, and there was nothing left of him but grubby little scraps of hypocrisy. Religion was just a stick to beat the soldiers with, and anyone who declared otherwise was full of pious drivel" (77).

This is the narrator's description of how World War I had transformed her father into an atheist. It occurs to me, however, that this is not the first time, nor the last, that God would "burst like a balloon." Certainly the next World War brought with it repeating images of a god who bursts in the face of his people, over and over again. And it seems that he continues to burst even today, despite our continued efforts to inflate and re-inflate him.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

California

Why do I get nothing done when I'm in California? I had planned to write every day, finish a book review, and finish reading two novels during my two weeks here. But I've done nothing, really. I did present at a conference in San Francisco (ALA), but nothing other than that. I haven't even seen half of my friends since I've been here, and it's nearly time to return to Indiana. And now, after reading a creepy article about the rise of anti-Semitism in Orange County, I am boycotting Newport Beach. I'm so disillusioned. Home is no longer home, and it's a very disappointing, and entirely unproductive, vacation.

Friday, June 02, 2006

Great American Books

This fall I get to teach a course called Great American Books, and so I have to figure out which great American books to teach. My favorite "friend" gave me one piece (among others) of excellent advice: end the course with Philip Roth's American Pastoral. I'm very excited about this. But now what do I teach for the first 14 weeks of the semester?

Now, I know that Melville has to be on the syllabus. He just has to. But, and I'm sorry Casey, I have always had trouble getting through Moby Dick. If it killed me when I was an undergrad (and grad student), won't it make my students want to kill me? I found myself discussing this today with my younger brother. He's 16 (much younger than me, as I slouch toward 30), and has read it twice, the first time when he was around age 10, which puts me to shame as, ironically, when I was that age I was memorizing entire books of the bible as if my life depended on it. But why is Moby Dick a greater American book than, say, Alice Walker's The Color Purple? When it comes to choosing which books are the American greats, like Bartleby, I prefer not to. Choose, that is.

But take one look at my overfilled bookshelves and it is clear that I do have an opinion regarding the great American books. Judging by the stacks of books not collecting dust, what I consider to be great American books have one thing in common: they are all Jewish. Many are obviously Jewish books (Philip Roth, Henry Roth, Cynthia Ozick), but others are a bit more sneaky in their connections to the covenant. People (even literati) are often surprised to discover that The Natural or Catch-22 were written by Jewish authors, or that Nathaniel West is a Jewish writer. But there's no denying that some of the best books of the century in this country have been penned by Jewish writers.

I can't, however, turn the Great American Books course into the Great American Jewish Books course. So here's what's on my list so far -- any advice would be greatly appreciated:

Melville: Moby Dick

Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Malamud: The Natural

Faulkner: Sound and the Fury

Morrison: Beloved

Roth: American Pastoral

Now, I know that Melville has to be on the syllabus. He just has to. But, and I'm sorry Casey, I have always had trouble getting through Moby Dick. If it killed me when I was an undergrad (and grad student), won't it make my students want to kill me? I found myself discussing this today with my younger brother. He's 16 (much younger than me, as I slouch toward 30), and has read it twice, the first time when he was around age 10, which puts me to shame as, ironically, when I was that age I was memorizing entire books of the bible as if my life depended on it. But why is Moby Dick a greater American book than, say, Alice Walker's The Color Purple? When it comes to choosing which books are the American greats, like Bartleby, I prefer not to. Choose, that is.

But take one look at my overfilled bookshelves and it is clear that I do have an opinion regarding the great American books. Judging by the stacks of books not collecting dust, what I consider to be great American books have one thing in common: they are all Jewish. Many are obviously Jewish books (Philip Roth, Henry Roth, Cynthia Ozick), but others are a bit more sneaky in their connections to the covenant. People (even literati) are often surprised to discover that The Natural or Catch-22 were written by Jewish authors, or that Nathaniel West is a Jewish writer. But there's no denying that some of the best books of the century in this country have been penned by Jewish writers.

I can't, however, turn the Great American Books course into the Great American Jewish Books course. So here's what's on my list so far -- any advice would be greatly appreciated:

Melville: Moby Dick

Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Malamud: The Natural

Faulkner: Sound and the Fury

Morrison: Beloved

Roth: American Pastoral

Sunday, May 21, 2006

Hashish and Illumination

I just read an interesting essay on Walter Benjamin that explores the possibility that drug experimentation illuminated Benjamin's thinking: "The missing link in Benjamin's work seems to have been supplied, at least in part, by the experience of rausch, the chemically induced trance state of intoxication."

One question immediately flashed through my mind: is this why I can't finish my paper on Steve Stern and Nathan Englander? Do I need hashish (I'm not really even sure what that is)?

Probably not, and if so I suppose I'm not destined to generate work on par with the brilliance of Benjamin, for whom "each sentence seems to bear almost scriptural weight, fitting for a man who conceived of a present 'shot through with splinters of messianic time.'"

This was something I didn't know about Benjamin, and it makes me wonder about others -- what about Blanchot and Derrida? Are their illuminations also elucidated by a special enhancer? I hate to think so...

One question immediately flashed through my mind: is this why I can't finish my paper on Steve Stern and Nathan Englander? Do I need hashish (I'm not really even sure what that is)?

Probably not, and if so I suppose I'm not destined to generate work on par with the brilliance of Benjamin, for whom "each sentence seems to bear almost scriptural weight, fitting for a man who conceived of a present 'shot through with splinters of messianic time.'"

This was something I didn't know about Benjamin, and it makes me wonder about others -- what about Blanchot and Derrida? Are their illuminations also elucidated by a special enhancer? I hate to think so...

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Colonizing Heaven

Recently, my friend Casey asked me to look at an essay by E.M Cioran called "A People of Solitaries." It's an essay about the Jewish people in which, as Susan Sontag suggests in the introduction to the book, he demonstrates a "startling moral insensitivity to the contemporary aspects of his themes." The interesting thing, is that I skimmed through a few of the other essays in the book and like what I see; Cioran's stuff is somewhat addictive.

But here are a few of the most shocking lines (and my commentary) from this particular essay:

"Is this people not the first to have colonized heaven, to have placed its God there?" Now, call me crazy, but it seems a little gross to suddenly characterize the Jews -- a group of people who have been persecuted from the beginning, and people who until very recently did not even have a homeland -- as colonizers of anything, let alone heaven. This is one of the most insensitive statements one could make, to characterize the Jews as imperialists of heaven. In fact, Judaism is one of the few religions that doesn't actively seek proselytes. They don't send out evangelists into all corners of the earth in search of converts. They don't force their religion, or way of life, on others the way that "colonizers" would. Regardless of Ciroan's intentions, I think this statement contributes to anti-Semitism in yet another way.

"The most intolerant and the most persecuted of peoples unites universalism with the strictest particularism." From what I can tell, this essay was published not too long after the Holocaust. How is it possible to, in the wake of such a disaster, conceive of the Jewish people as as intolerant as they are persecuted?

"Although chosen, the Jews were to gain no advantage by that privilege: neither peace nor salvation . . . Quite the contrary, it was imposed upon them as an ordeal, as a punishment. A chosen people without Grace. Thus their prayers have all the more merit in that they are addressed to a God without an alibi." This is one of the things in this essay that is worth thinking seriously about. I'm not sure what he means about their prayers having more merit, but the concept of the prayers being addressed to a a God who has no alibi is interesting, and hints of other discussions of the end of theodicy -- the end of trying to conceive of a God who is good. The end of trying to make excuses for God in the wake of the Holocaust. But later in the essay, it seems that Cioran is blaming the Jews for inventing a God who would turn his back on them.

There are other things I could write about here, but this is already getting too long. An interesting thing towards the end of this essay -- Cioran reveals his own ambivalent relationship to the Jews, describing how at one point he may have wished to be a Jew, and at another he loathed Jews.

But here are a few of the most shocking lines (and my commentary) from this particular essay:

"Is this people not the first to have colonized heaven, to have placed its God there?" Now, call me crazy, but it seems a little gross to suddenly characterize the Jews -- a group of people who have been persecuted from the beginning, and people who until very recently did not even have a homeland -- as colonizers of anything, let alone heaven. This is one of the most insensitive statements one could make, to characterize the Jews as imperialists of heaven. In fact, Judaism is one of the few religions that doesn't actively seek proselytes. They don't send out evangelists into all corners of the earth in search of converts. They don't force their religion, or way of life, on others the way that "colonizers" would. Regardless of Ciroan's intentions, I think this statement contributes to anti-Semitism in yet another way.

"The most intolerant and the most persecuted of peoples unites universalism with the strictest particularism." From what I can tell, this essay was published not too long after the Holocaust. How is it possible to, in the wake of such a disaster, conceive of the Jewish people as as intolerant as they are persecuted?

"Although chosen, the Jews were to gain no advantage by that privilege: neither peace nor salvation . . . Quite the contrary, it was imposed upon them as an ordeal, as a punishment. A chosen people without Grace. Thus their prayers have all the more merit in that they are addressed to a God without an alibi." This is one of the things in this essay that is worth thinking seriously about. I'm not sure what he means about their prayers having more merit, but the concept of the prayers being addressed to a a God who has no alibi is interesting, and hints of other discussions of the end of theodicy -- the end of trying to conceive of a God who is good. The end of trying to make excuses for God in the wake of the Holocaust. But later in the essay, it seems that Cioran is blaming the Jews for inventing a God who would turn his back on them.

There are other things I could write about here, but this is already getting too long. An interesting thing towards the end of this essay -- Cioran reveals his own ambivalent relationship to the Jews, describing how at one point he may have wished to be a Jew, and at another he loathed Jews.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

The Ghostwriter

I'm tired of writing my conference paper, and so Eliot Epstein is taking over. It's his fault if there's too much Slavoj Zizek in my paper and not enough Emmanuel Levinas. We've been going at it all night: aesthetics vs ethics. Note the insane look in Eliot's eyes, his crazy hair falling into his face.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Don't Look Back

Recently a girlfriend confided in me that she may be in love with two men at the same time for completely different reasons. She looked to me for advice, a reason to allow the scales to tip one way or another -- a way out of the erotic dilemma. I felt for her, and yet I also sensed something enviable in the way she allowed herself to experience the fullness of life in multiple directions, the way she allowed herself to be extended in different directions without breaking. I wanted to tell her she didn't have to choose, that she need only feel and that would be enough, all anyone could ask of her. Forget logic, dispose of boundaries, confound reason.

I then thought of one of my favorite essays of all time as a way to help her validate the complexity of her desires.

In Rebecca Goldstein's 1992 essay "Looking Back at Lot's Wife," (Commentary) the story of Lot's wife in Genesis is examined. Goldstein suggests that while Irit may have looked back though God told her not to, it was because of her love for her daughters who remained there. She suggests that God may have turned Lot's wife into salt as a way of forgiveness.

But that isn't what I wish to talk about right now.

Goldstein describes a poignant conversation with her father: "He thought it was right for human life to be subject to contradictions, for a person to love in more than one direction, and sometimes to be torn into pieces because of his many loves. I suspect he even felt a little sorry for any great man of ideas who had cut himself off, so consistently, from what my father saw as the fullness of human life."

The fullness of human life. To love in more than one direction. To embrace human complexity and uphold it as the greatest aspect of being, well, human. But reality tells me that this can't work. Yes, the lover who has extended him/herself in two directions may feel the pain of being torn into millions of pieces, but what about the two people who he/she loves? Aren't they also torn considerably, and in a way far less easier to piece back together? Doesn't it require that the lover deceive them at times in order to maintain the "love" or the relationship(s)? Doesn't the lover ultimately rob the the ones he/she loves of the capacity to love in the same way? It doesn't seem like a fair trade.